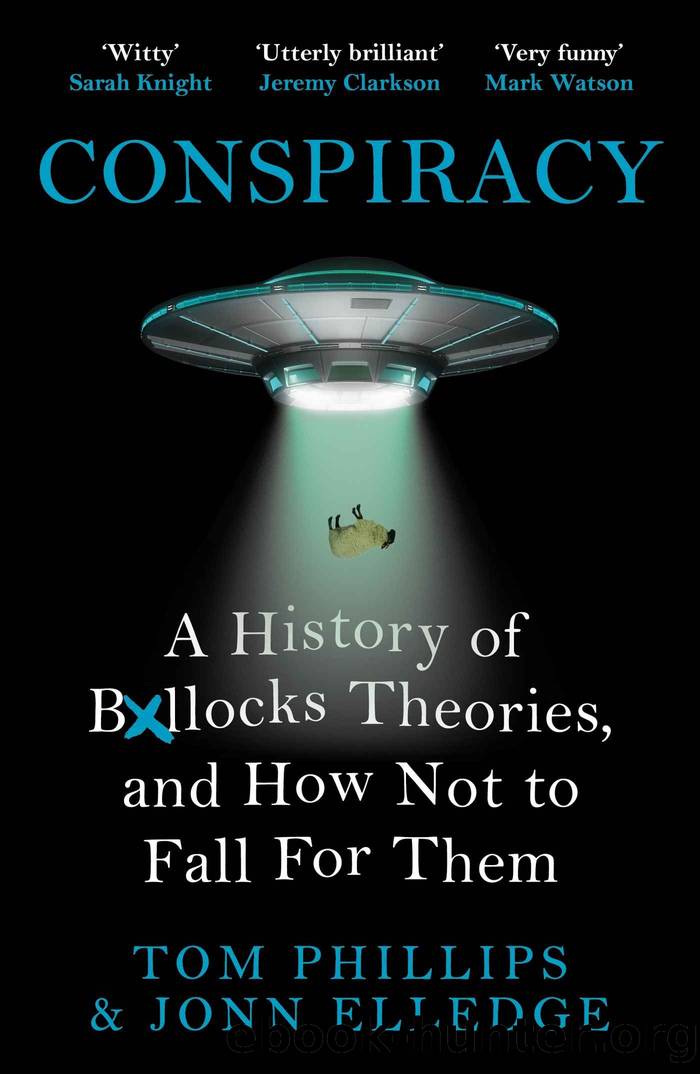

Conspiracy by Tom Phillips & Jonn Elledge

Author:Tom Phillips & Jonn Elledge [Phillips, Tom && Elledge, Jonn & Phillips, Tom && Elledge, Jonn]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Headline

Published: 2022-07-07T04:00:00+00:00

Itâs worth pausing here for a moment to ask why, exactly, do pandemics attract conspiracy theories in this way?

Partly itâs because the fear of disease â more broadly, the fear of contamination and contagion â is among the most deeply rooted and primal of our fears. And conspiracy theories that draw on primal fears are well set to spread like wildfire. Our instinct to avoid things that might harm us is incredibly powerful â itâs why we find the sight or smell of rotting food repellent, and why we may feel a strong aversion to people who appear sickly.

This isnât just limited to disease, of course. As with the well-poisoning manias of the Middle Ages, panics about contaminated food or drink have been common throughout history â for example, in Belgium in June 1999, when the government banned Coca-Cola for two weeks amid a nationwide scare that it was making people ill. (Investigations later concluded that these fears were baseless.) These panics can sometimes rise to the level of conspiracy theory; a few years before the Belgian Coke panic, a series of scares about deliberately contaminated chewing gum sprang up in the Middle East, first in Egypt, in 1996, then again a year later in the Palestinian territories. This gum was supposedly tainted with hormones that would drive the youth into sexual frenzy; perhaps unsurprisingly, Israel was blamed. (Thereâs no evidence to suggest that this supposed psychoactive sex gum was ever actually a thing.)30

Such contamination fears lie behind some of our more enduring conspiracy theories. The fear of chemtrails rests on a fear that our very air is being surreptitiously poisoned for some nefarious purpose. Likewise, while the long-running arguments about adding fluoride to water supplies isnât necessarily conspiratorial in nature â thereâs a legitimate debate to be had about basically any public health measure, even if the medical consensus is largely in favour of fluoridation â it can definitely tip over into conspiracism: for example, when itâs suggested that fluoridation is a tool of population control, or that, as one right-wing periodical put it in 1960, âfluoridation is known to Communists as a method of Red warfareâ.31

But this fear of contamination and contagion, powerful as it is, isnât the only explanation of why disease outbreaks tend to spark conspiracy theories. Itâs also because disease outbreaks are almost perfectly set up to trigger our instinctive disbelief that massive events can have small or random causes.

For a long time, of course, we didnât even know what the causes of many diseases were. But even now we do know â about parasites and bacteria and viruses and what-have-you â they still donât feel like a satisfying explanation for a pandemic, especially when youâre stuck in the middle of one of the bloody things. How can these huge, world-changing events â which upend lives, kill on a vast scale and reshape the very fabric of society â possibly be caused by something thatâs literally invisible to the naked eye? A molecule gets copied

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Spell It Out by David Crystal(36110)

Professional Troublemaker by Luvvie Ajayi Jones(29651)

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19058)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19035)

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15339)

The Goal (Off-Campus #4) by Elle Kennedy(13658)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12187)

The Break by Marian Keyes(9358)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9280)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8981)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8894)

Educated by Tara Westover(8047)

The handmaid's tale by Margaret Atwood(7757)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7330)

Win Bigly by Scott Adams(7184)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6877)

The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion(6381)

Six Wakes by Mur Lafferty(6243)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5761)